“What safeguards our solar system is our star. The sun provides a shield stretching  beyond the last planet in its orbit..a force field that deflects these cosmic rays. But these solar winds can be dangerous, too. Especially during outbursts called coronal mass ejections. Want a vision of Earth gone wrong? Just look at what solar storms do to our sister planet, Venus.”

beyond the last planet in its orbit..a force field that deflects these cosmic rays. But these solar winds can be dangerous, too. Especially during outbursts called coronal mass ejections. Want a vision of Earth gone wrong? Just look at what solar storms do to our sister planet, Venus.”

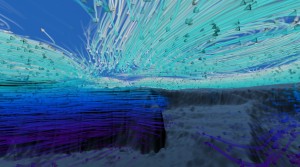

That is the opening narration (by actor Liam Neeson) of the NASA film, “Coronal Mass Ejection and Ocean/Wind Circulation”, that has won first place in a contest sponsored by the National Science Foundation and Science Magazine. What follows are outstanding animations of cosmic particles spreading across the solar system and sweeping around Venus and the Earth. The video goes on to explain how Earth has avoided the fate of Venus and then describes how most of the solar energy is deflected but what is absorbed is enough to drive our climate. The latter is illustrated by animations of wind and ocean currents, such as the Gulf Stream. This video is an excerpt from a larger movie called the Dynamic Earth, which is being shown in planetariums around the world.

Watch the winning video (with Liam Neeson narration): http://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/goto?11003

Watch the version submitted to contest on YouTube:

More about Dynamic Earth: http://www.dynamicearth.spitzcreativemedia.com

More about the International Science and Engineering Visualization Challenge: http://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/scivis/index.jsp

Image Credit: Still from “Dynamic Earth”, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center http://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/goto?11003

The NASA video and most of the videos that won Honorable Mention in this contest were created by skilled teams of animators and videographers. However, one of the Honorable Mentions was produced by a team of scientists led by Geoffrey Harlow, a biology student: